Link to the conference site | CSD

The Way of the Heart--

Journeys of Transformation

Paul Beirne Talk 2

The Donghak Way

I wish to introduce you to a man.

This man did not ever leave the confines of his own country; he founded a new Way which, as its central tenet, espoused  an intimate, personal relationship with the Lord of Heaven; he promulgated this Way for approximately three years; he was arrested by authorities as an apostate, was tried and brutally executed; his few followers fled and hid from sight. And this was just the beginning of an all but extinct religious movement which was revived and spread throughout the country like wild-fire.

an intimate, personal relationship with the Lord of Heaven; he promulgated this Way for approximately three years; he was arrested by authorities as an apostate, was tried and brutally executed; his few followers fled and hid from sight. And this was just the beginning of an all but extinct religious movement which was revived and spread throughout the country like wild-fire.

Does this story sound familiar?

I met this man at a turning point in my life, when I had left a known and secure lifestyle and took a direction which was totally unknown, frightening and at the same time, exciting. I first heard his name in a lecture on Korean History at Yonsei University in Seoul where I was undertaking a Masters degree in East Asian Studies.

The person’s name is Choe Jae-son, who later changed his name to Choe Je-u and was known to his followers by the pseudonym Su-un: ‘Watercloud’. For convenience sake I will refer to him by pseudonym for the remainder of this talk. Su-un’s life, for the most part, was one of abject failure. Perhaps this is why I was immediately drawn to him when I first heard his name. Curious, isn’t it, how we meet wisdom figures at just the right intersection in our journeys of transformation when we do have the opportunity to change direction and walk with them.

Su-un was born in 1824 to a neo-Confucian nobleman, Choe-ok. Advanced in years, Choe-ok had attempted to have a  son to hand on his inheritance, but due to the untimely death of his first and then his second wife, he was unable to do so. Late in life, Choe-ok married a widow, Madame Han, who bore him a son, Su-un. His parents’ initial joy at the birth of a son was tempered by the fact that, firstly, the lineage into which their child was born had been out of favour for generations in what is termed the internecine royal in-law politics of the day. Secondly, he was the son of a disenfranchised nobleman and a widow, which in a strict neo-Confucian society, while not strictly illegal, relegated the child to the status of a seoja—of illegitimate descent, a non-person, who did not even register on the neo-Confucian hierarchical structure of Korea. Consequently, Su-un was prohibited from studying for, or undertaking the rigorous Civil Service examination, success at which enabled a young person to begin to scale the Korean social pyramid.

son to hand on his inheritance, but due to the untimely death of his first and then his second wife, he was unable to do so. Late in life, Choe-ok married a widow, Madame Han, who bore him a son, Su-un. His parents’ initial joy at the birth of a son was tempered by the fact that, firstly, the lineage into which their child was born had been out of favour for generations in what is termed the internecine royal in-law politics of the day. Secondly, he was the son of a disenfranchised nobleman and a widow, which in a strict neo-Confucian society, while not strictly illegal, relegated the child to the status of a seoja—of illegitimate descent, a non-person, who did not even register on the neo-Confucian hierarchical structure of Korea. Consequently, Su-un was prohibited from studying for, or undertaking the rigorous Civil Service examination, success at which enabled a young person to begin to scale the Korean social pyramid.

Su-un entered into an arranged marriage at the age of 13, purportedly against his will. Although classically trained by his father, all avenues to legitimate occupations were closed to him. Su-un’s mother died when he was six and his father when he was 16. His father’s house and extensive library subsequently burned to the ground, and Su-un was forced, humiliatingly, to move his family into his parents-in-law’s house. After several unsuccessful commercial ventures, and a brief and unhappy stint as a teacher, Su-un was left with little choice but to wander the land selling household wares.

It was during this time that Su-un discovered a country on the brink of collapse and decaying internally. The moribund 700 year old Yi dynasty hung precariously like a decaying piece of fruit on a dying tree. Unscrupulous and unchecked, rogue landlords squeezed every last ounce of resources and dignity from a peasant population which deserted their homes and villages and either fled from, or took up, lives of brigands. Famine, rebellions and epidemics spread unchecked while and the attention of the ruling classes were totally focussed on their own survival.

Externally, following the Opium Wars with Britain, Korea’s patron China was in the process of being carved up by colonizing European powers, and foreign warships were already appearing on Korean shores. To the East, the Tokugawa era was approaching its end in Japan and the Meiji Restoration had begun, which would see Japan blossom into a major world power. Korea then was caught in a pincer movement between established and emerging powers, with neither the resources nor the willpower to counter them.

In brief, Su-un experienced firsthand a nation on the brink of total chaos with negligible promise for the future. It probably occurred to him in his wanderings that he was a living metaphor of the land through which he wandered.

It was during his wanderings that an idea began to germinate in Su-un’s mind. Specifically, because the once powerful neo-Confucian tradition and ethic that purported to guide the country was now corrupted and collapsing, and because the foreign powers which stood ready to swoop and invade the country were supported by a powerful spiritual force/religion which he termed Seohak (Western Learning), that is, Catholicism, the only chance that his country had for survival was through the establishment of a powerful spiritual force to counteract Catholicism. It was this spiritual movement that Su-un felt a deep call to establish.

Typically, his initial efforts to become enlightened and to establish what he called a new Way, ended in abject failure. After severally failed attempts to achieve enlightenment, Su-un finally decided to risk everything in order to achieve his goal. He left his wife’s natal home and took his family to his father’s retreat deep in the Kumi mountains near the ancient capital of the Silla dynasty of Gyeongu in South Eastern Korea. He stated in his writings that he would not leave this place until ‘something’ happened.

decided to risk everything in order to achieve his goal. He left his wife’s natal home and took his family to his father’s retreat deep in the Kumi mountains near the ancient capital of the Silla dynasty of Gyeongu in South Eastern Korea. He stated in his writings that he would not leave this place until ‘something’ happened.

- It was at this scenic retreat that Su-un changed his name, from Jae-son (the name that was bestowed on him at his birth) to Je-u, ‘the saviour of the ignorant’, clearly indicating his intentions to make a ‘great resolution’ and lead the disenfranchised populace of Korea to a new spiritual Way of living. But his change of name had no effect on his situation or on his condition.

- It was as he was sitting beside the Dragon Pool at Mt Gumi lamenting his sorry state, his ambitions crushed, with nowhere to turn, at the nadir of his life, that Su-un came to a deep insight regarding the name which he had adopted. He wrote:

“As I silently contemplated, my thoughts turned to my new name; sitting looking foolish, my appearance resembled my name and its meaning became clear to me.”

In other words, Su-un realised that his new name was inclusive rather than exclusive, and that before he do anything else he first had to acknowledge that he was as ignorant, as lost and in need of saving as the most vulnerable and ‘foolish’ as his compatriots.

- Immediately after this revelation, on the cusp of Spring in 1860, in the middle of the night, in a tiny hut secreted deep in remote mountains, surrounded by his family, Su-un experienced an epiphany which changed and transformed his life and affected the lives countless numbers of his compatriots for generations to come.

- Su-un wrote three accounts of this ecstatic experience in his two volumes of scriptures: Yongdam Yusa: Reflections of the Dragon Pool, written in Korean, in Kasa verse form which facilitated memorization and communication by the common people; and Dongyeong Daecheon: The Great Collection of Eastern Scriptures, written in classical Chinese script for the literati of Korea.

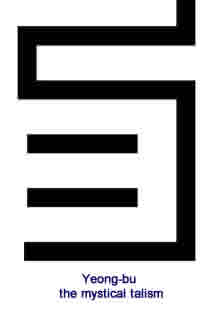

Time does not permit further commentary on these scriptures. Suffice it to say that embedded in them are two fundamental symbols, the Jumun, a Sacred Incantation; and the Yeongbu, a Mystical Talisman through which he communicated the core teachings of his new Religion, which he named Donghak: Eastern Learning, as distinct from Western Learning: Catholicism.

I will concentrate on this latter symbol in an effort to explain the genius of Su-un as a religious innovator and a mystic of extraordinary creativity, insight and sensitivity.

I will concentrate on this latter symbol in an effort to explain the genius of Su-un as a religious innovator and a mystic of extraordinary creativity, insight and sensitivity.

Su-un adapted and adopted the Yeoung-bu from an ancient book of prophecy, the Cheonggam-nok, the Book (prophecy) of Cheongnam. This book was very popular in Su-un’s time as it predicted the end of the Yi Dynasty and the birth of a messianic royal figure, the Jin in (True Man), who would found a new dynasty based on justice, ethics, compassion and equality, which would last for 1000 years.

The Cheonggam-nok predicted and described in symbolic and frightening language the apocalyptic times that were to come in the immediate future. White rainbows would appear in the sky, stars would plummet from the heavens, bodies would block streams and great armies with their war machines would wreak havoc on the land. In the midst of this chaos, death and destruction there were, however, 10 secret places of refuge which offered peace and security for those lucky enough to find them. The search for these harbours of refuge was endemic throughout Korea, from the richest noble to the poorest peasant. The key to finding these refuges, as referenced in the Cheonggam-nok, depended on the Chinese characters, gung gung or eul eul gung gung. These were the keys to finding peace, security, and by extension prosperity. The only advice that the Cheonggam-nok gave to interpreting them was:

“If you wish to know the location of eul eul gung gung, it is on the outskirts of a metal bird and a wooden rabbit.” (‘Metal bird’ and ‘wooden rabbit’ are obscure references to the Chinese method of measuring time).

Welcome to the frustratingly arcane language of Korean apocalyptic literature.

What did Su-un do with this obscure reference? He took the term eul eul gung gung, which actually form half the Chinese character for Yak—meaning ‘weak’ and renamed it the Yeongbu, ‘ mystical talisman’. He called this talisman ‘the elixir of immortality’ and wrote ‘the elixir of immortality is in my heart, its shapes are gung and ul”.

What Su-un did, quite simply, was brilliant. He took the symbol that represented the most sort-after place of refuge in Korea in a time of apocalyptic chaos, destruction and death, and placed in firmly and centrally, not in some secret geographical location, but in the human heart. Why?

Because the Lord of Heaven permanently resides there.

This intimate union of humanity and Divinity is expressed in a seminal statement and question by the Lord of Heaven to Su-un, recorded in Chapter 6 of his book, Nonhak-mun: Discussion on Learning, as follows:

In Korean, the Lord of Heaven asked Su-un: O Sim chuk Yeo Sim:

“My heart is your heart.”

And then the Lord of Heaven said: “How can humankind know this?”

This was the impetus for Su-un to found his Way. The way to become aware of this presence of the Lord in one’s heart was to practice the ritual of the Yeongbu. The ritual involved the drawing of half of the Chinese character for Yak, meaning weakness; but Yak in Korean also means ‘medicine’, in fact, Su-un refers to the Yeongbu as Sacred Medicine (a Daoist concept).

Su-un taught his followers to meditatively write this character Yak on a piece of paper, burn the paper, mix the ashes in pure water, and then drink the mixture. This ritual represented the symbolic embracing and affirming of weakness, a concept of which Su-un was very familiar. And it is through the symbolic embracing of my weakness that I am cured. Why? Because I become aware of the healing presence of the Lord of Heaven in my heart.

By extension, the most powerful entity in the universe, the Lord of Heaven, is intimately familiar with weakness, and thus rules over the universe not only with infinite power, but with infinite compassion and restraint.

This is the Donghak Way: Since the Lord of Heaven

is intimately present in each person’s heart—‘my heart is your heart’-- each person, no matter their age, sex or status, is due ultimate and complete respect.

A society built on neo-Confucian hierarchical distinctions such as Korean society was at that time, could not tolerate the democratic principles imbedded in the Donghak Way.

After proclaiming his new Way, Su-un was condemned as a heretic, his teachings were proscribed, he was arrested, tried and was executed. His head was cut from his body and placed on a spear at the village of his birth. But the execution of the messenger did not kill the message. Following his death, and through careful nurturing by his followers, the Donghak religion spread to all corners of Korea, and culminated in the Donghak Peasant Rebellion in 1894. This Rebellion was suppressed by the King with military assistance from China and Japan. But the democratic principles fundamental to the Donghak Way could not be as easily eradicated.

Subsequent to the failed rebellion, Donghak was renamed Cheondo-gyo, the Religion of the Heavenly Way, and the Donghak/ Cheondo-gyo principals of equality formed the basis of the Korean Declaration of Independence promulgated on March 1, 1919. Of the thirty-three leaders who signed the declaration, publicly promulgated it and were summarily arrested by the Japanese who occupied the Korean peninsula, fifteen were Donghak/Cheondo-gyo members, and the chief signatory and organizer of the group was Son Byeong-hi, the third leader of the religion that Su-un founded.

In the next session, I would like to recount briefly how I journeyed to the spot in the Kumi mountains, at the Youngdam Pavilion where Su-un experienced his ephiphany, to ‘find’ Su-un at the location of his seminal encounter with the Lord of Heaven. This journey, to say the least, was full of surprises.