Link to the conference site | CSD

The Way of the Heart--

The Way of the Heart--

Journeys of Transformation

Paul Beirne Talk 1

The Daoist and Buddhist Way

I very grateful for the opportunity today to take a few steps with you along the Way of the Heart, on our journeys of transformation.

Fundamental to this journey is the concept of the Way and we will begin our discussion today by considering how the Way is envisaged in East Asia. Let’s begin our journey with the Daoist concept of the Way. The Daoist Way was originally articulated in the Dao De Jing, the book which incorporates the  classic thought of Daoism, and a book which exhibited a strong influence on Confucianism and neo-Confucianism, Buddhism and other Oriental religions. The Dao De Jing was purportedly written by Lau Tzu (‘old man’) representing a wisdom figure and is most probably a compilation of sayings collected over decades.

classic thought of Daoism, and a book which exhibited a strong influence on Confucianism and neo-Confucianism, Buddhism and other Oriental religions. The Dao De Jing was purportedly written by Lau Tzu (‘old man’) representing a wisdom figure and is most probably a compilation of sayings collected over decades.

The Dao De Jing is composed of two books comprising approximately 5,000 Chinese characters, in other words, a very short book, and yet it is by far the most translated Chinese book.

The first character in the first sentence in the book is ‘Dao’ which is translated as ‘Way’. Daoism is ‘the School of the Way’.

The first characters in the book are translated as:

The Way that can be spoken of is not the constant Way (1)

The Way is forever nameless. (72)

The great Chinese scholar D. C. Lau, summarises: “There is no  name that is applicable to the Dao (the Way) because language is totally inadequate for such purpose.”

name that is applicable to the Dao (the Way) because language is totally inadequate for such purpose.”

This is a classic conundrum—How can one give a name to something that is nameless? Consequently, the Daoist Way, then, is an enigma wrapped in mystery shrouded in irony. Following the advice in the first sentence of the Dao De Jing, one should not attempt to explain the Dao, the Way, at any depth, or perhaps even at all. However, I urge you, if you have not already done so, to take the time to read and reflect on this profound book. (I recommend the translation by D. C. Lau, published by Penguin Classics, which is the closest to the original that I have encountered.) The Dao De Jing truly is a fascinating, mysterious and challenging book, which, if one does not try too hard, makes sense.

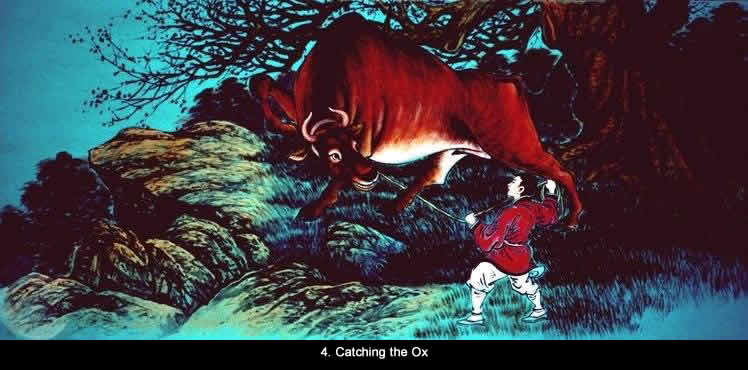

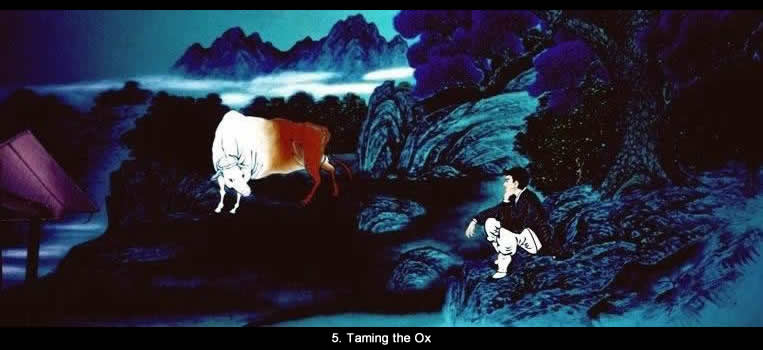

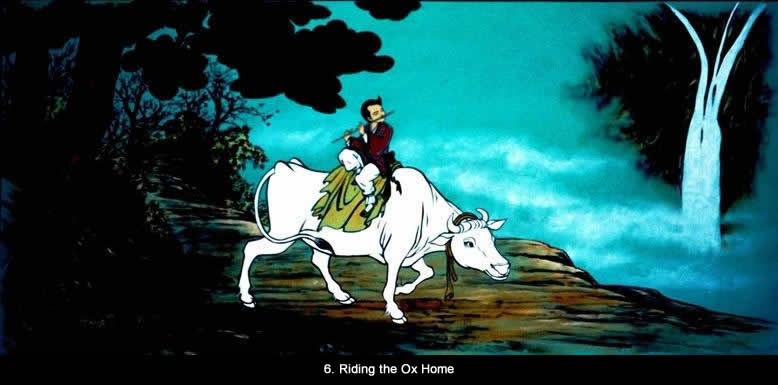

Perhaps this is the reason that the Ten Oxherding Pictures which we are about to consider are represented symbolically and pictorially, as they attempt to represent something that cannot be described in words. I should say that there is no direct link between the Ten Oxherding Pictures and the Dao De Jing, and one should not identify the Dao with the Pictures. However, originally, in their earliest versions, the pictures are a Daoist rather than Buddhist representations, and feature an elephant rather than an ox.

But the Dao De Jing and the Ten Oxherding Pictures have this in common, they both wrestle with concepts and images which reflect the spiritual Way that many of us seek, and find difficult to express.

The pictures that are represented today are photographs taken at the Cheonju Buddhist Monastery in South Korea, by a friend and colleague of mine, David Mason, who has lived in this country for 27 years and has immersed himself in history and the religions, and in particular, the folk religions of this Korea. His nom d’plume is ‘mountain wolf’, which is very appropriate, as he is very much at home in the peaks and valleys of the Korean mountains, and with the spirits that dwell there. David is a Professor of Cultural Tourism at Kyunghee University in Seoul.

The Ten Oxherding Pictures, Sip-u-do in Korean, appear in panels around the main Dharma Hall at all Buddhist monasteries in Korea, and represent the Buddhist Way to enlightenment.

The search depicted in the Oxherding Pictures is for one’s immutable centre, the original, hidden nature of one’s being. The quest is internal, not external and not strictly relational—it is a quest for union with an external Divine entity. That said, I think that you will find that the quest resonates for all those undertaking a journey of transformation.

Points to note:

- The changing the colour of the Ox as it is ‘tamed’, from fiery red to white, as one’s consciousness is tamed and quietened.

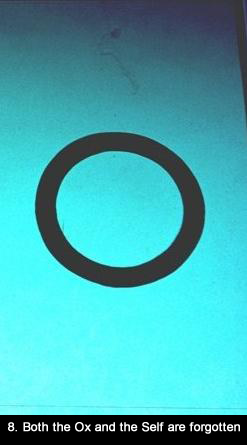

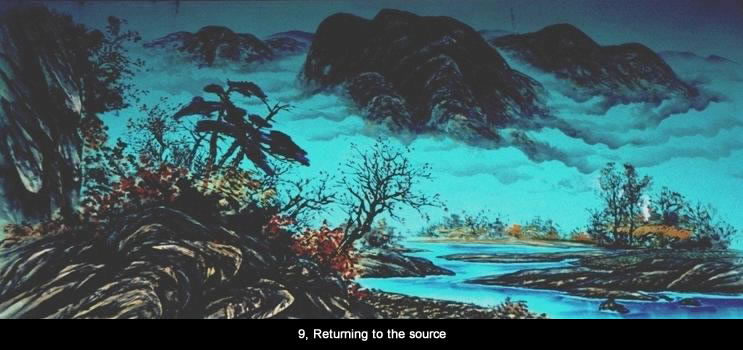

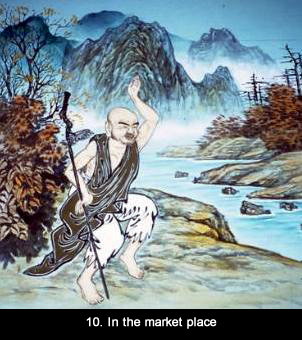

- Figures 8, 9 and 10—the complete circle, harmony with nature, return to the market place-- are not sequential, but represent different aspects of the same reality.

- Notice the age of the seeker from young to old, not literal of course, but representative perhaps of growth in wisdom and understanding as the interior struggle progresses and is resolved.

- The seeker, dusty and dishevelled in appearance, returns to the world transformed, and trees blossom as she/he passes by.

Question: How might these pictures relate to the interior struggle we experience to rid ourselves of distracting thoughts and images as we follow our Way? Does one of them in particular resonate more than the others at this part of your journey?

Ultimately, words are inadequate here. This is why this Buddhist quest is represented symbolically in pictures, as the Dao is represented in the Dao De Jing in mysterious, enigmatic language. As with the Dao, one must resist the temptation to explain the pictures at any depth. They are what they are. What are they to you? (An answer in the form of a Zen Buddhist koan is very appropriate.)